February 2020’s entry is by Alice Bates, who wrote her UCA Undergraduate thesis on Hemingway’s Paris and Kerouac’s New York…..

Hello, I’m Alice. I started my Architecture BA at the University for the Creative Arts in 2016 and graduated in June 2019. Prior to studying at UCA I completed a degree in Classics at the University of Cambridge. By reading plays, philosophical dialogues and poems in the original Greek I explored how architecture and urban planning helped enable the ancient Athenians’ remarkable way of life. Learning about the significance of innovative public space to the success of ancient Athens sparked my interest in the power of good city design. During my architecture degree I continued to explore the power of well-designed public space to bring people together and to create powerful shared experiences. I have found isovists an exciting tool to help further my exploration of city spaces and the way that we experience them. I am currently in the process of applying to study my Master of Architecture where I hope to continue using ‘isovistics’ to further my exploration of cities and public space.

“Paris Street, Rainy Day” by Gustave Caillebotte (1877).

How does the spatial form of a city influence its creative output? Exploring how cities and the spaces within cities inspire creatives and their networks.

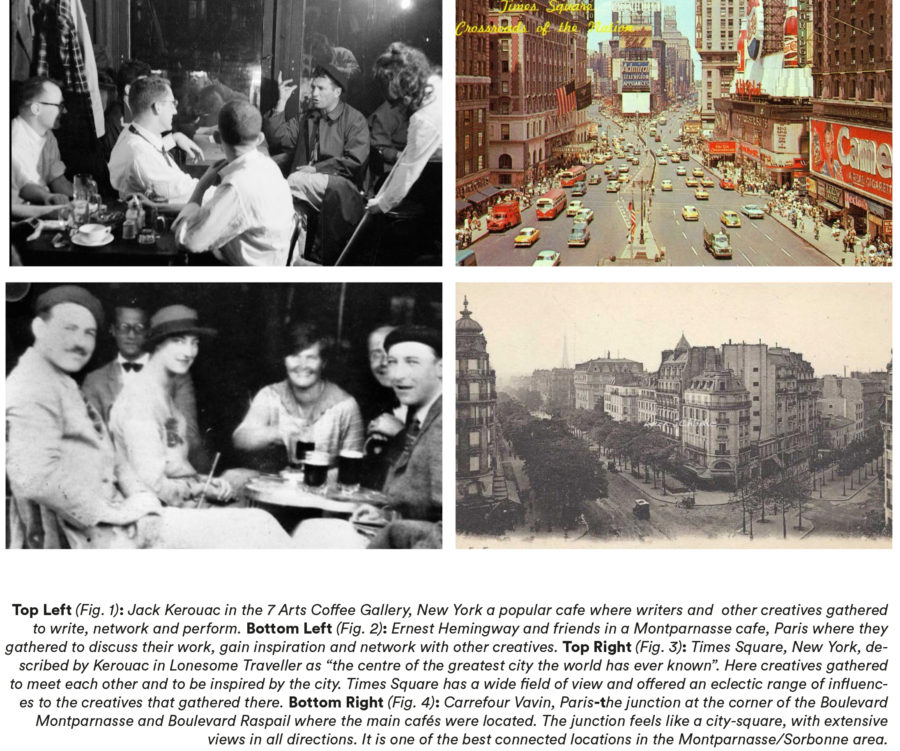

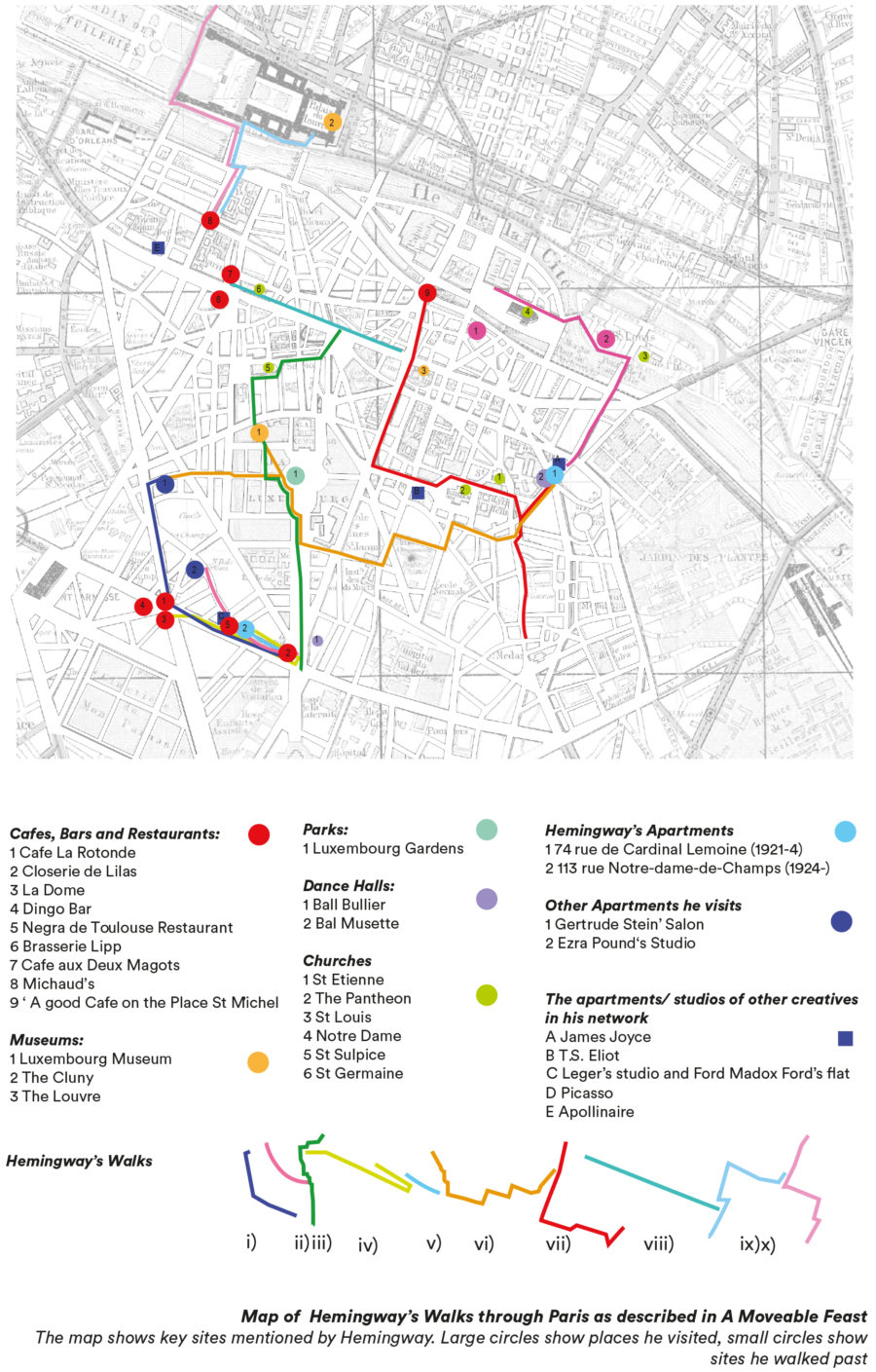

I used the Isovist software as a research tool for my undergraduate thesis at UCA’s Canterbury School of Architecture. My thesis explored the way in which the spatial layout of a city, or a neighbourhood within a city, might generate, motivate or enhance creative communities. It explored early 20th century Paris and mid-20th century New York- two cities associated with an extraordinary creative output. The research sought to establish how the spatial morphology of these cities has contributed to their success as artistic and cultural centres. My study explored Paris and New York through the eyes of the creatives that inhabited them. The research centred around two first-hand written accounts: A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway for Paris and Lonesome Traveller by Jack Kerouac for New York. I then used ‘isovistic’ research methods to further analyse each city, focussing on key locations identified by Hemingway and Kerouac and testing for spatial qualities that might explain their significance to creative communities.

The Isovist software was central to my research. Whereas narrative sources provide a more sensual and poetic understanding of a city, isovists provided a science-based method of analysing and quantifying space and its configuration.

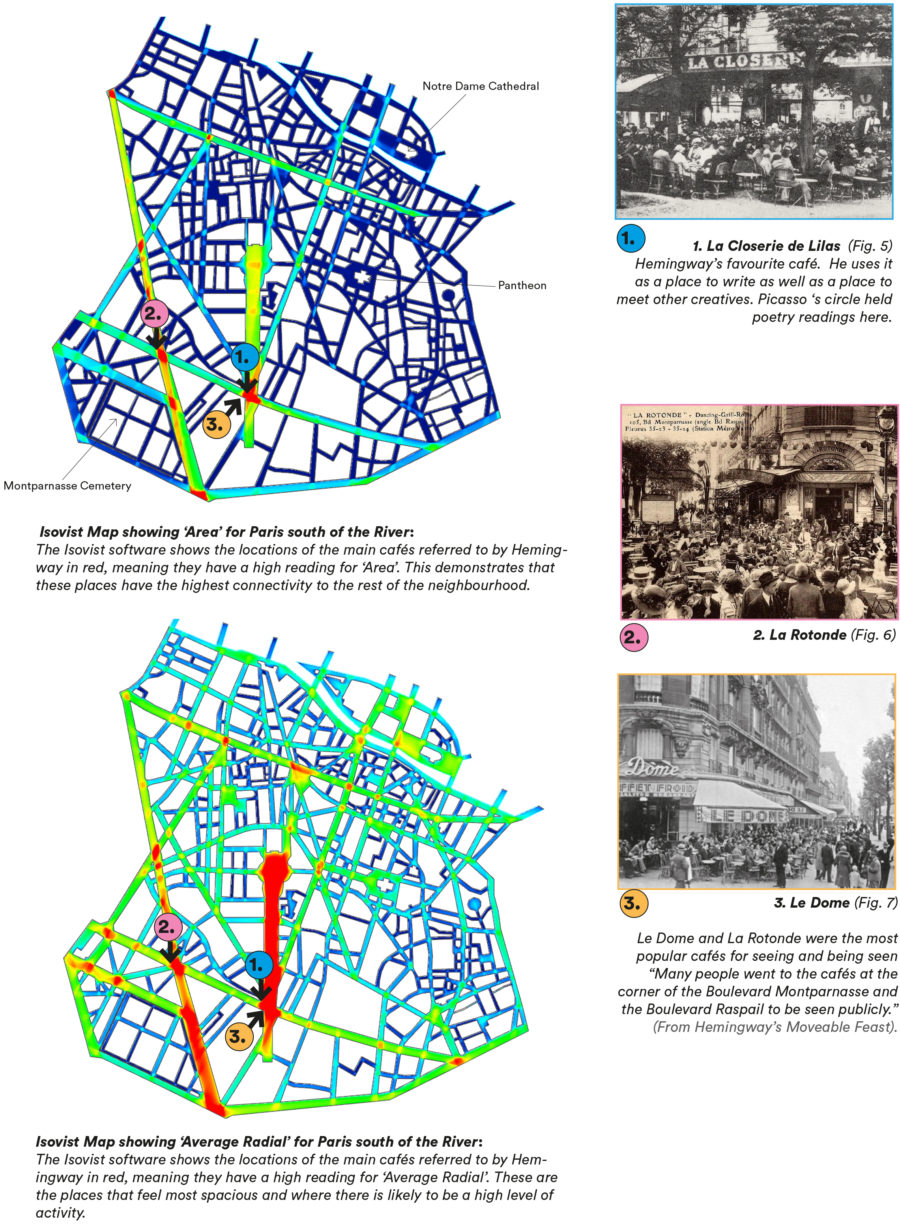

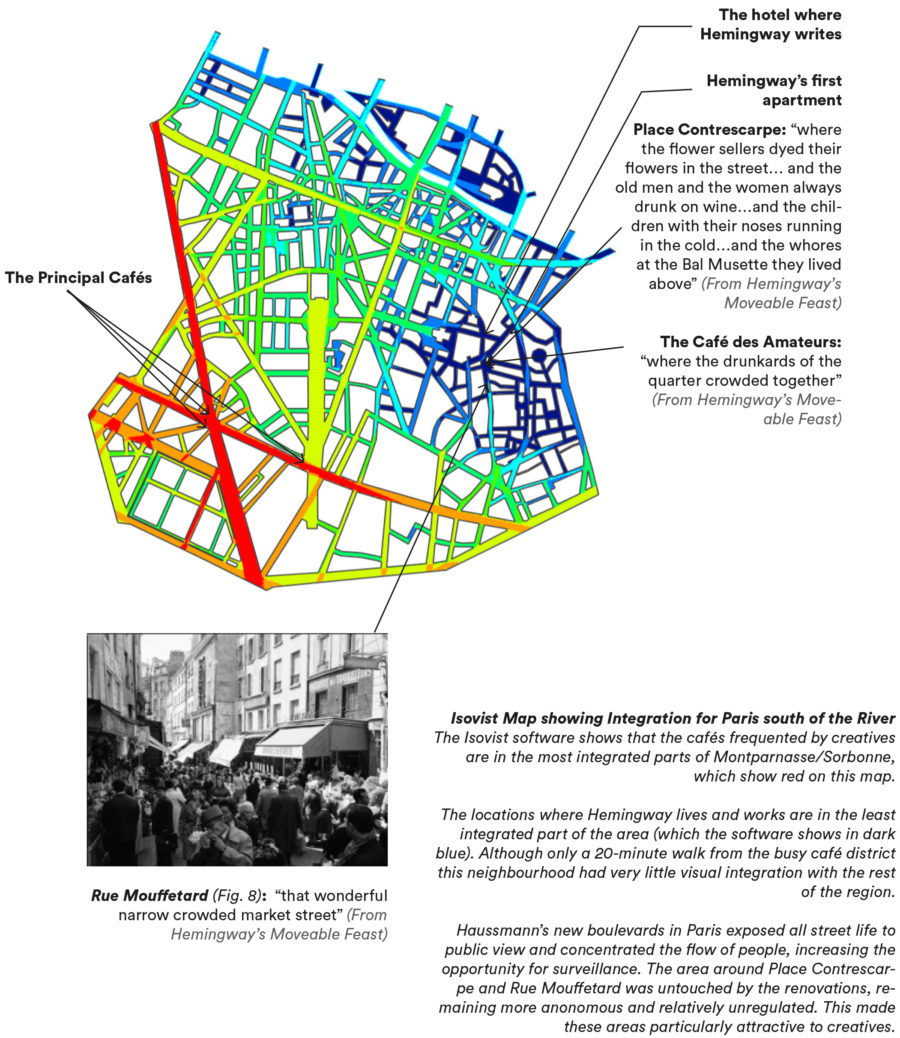

I traced maps of Paris’ left bank in the 1920s and Manhattan in the 1950s and ran them through the isovist software, testing for a series of different spatial characteristics. The results provided mappings that demonstrated what the field of view would be like as you moved through each city. Where is your view widest? Where can you be viewed most clearly? How far can you see? How rapidly does your view change? Each of the questions corresponded to a defined measure, which the Isovist software analysed, mapped and colour coded. I also used Isovist mappings to test for levels of connectivity and integration across key neighbourhoods in both cities. This enabled me to understand how these neighbourhoods functioned more broadly. I was particularly interested in how pathways within each area are stitched together and how this might impact wayfinding within each city.

At the same time, I mapped the routes Hemingway and Kerouac described taking through their respective cities. Following the tradition of 19th and 20th century flaneurs, surrealists and derivists, I sought to use subjective experience to generate objective knowledge about a place. By reading Kerouac and Hemingway’s writings I identified the key places where they met up with other creatives, the places where they wrote and the places they visited to seek inspiration. I then compared the findings of the Isovist analysis with the locations described in these first-hand accounts.

Intruigingly, almost every significant location mentioned by Hemingway and Kerouac in their writings were flagged up by the Isovist software as spatially interesting locations.

My results demonstrated that there appear to be a series of spatial characteristics found in Paris and New York that have a strong correlation with the presence of creatives. These seem to stem from the creatives’ desire to capture an audience, to see and be inspired by the city and its inhabitants and to meet and develop social networks. Also of importance is the ability to access a wide range of influences within a walkable space and, finally, the ability for creatives to withdraw into a more private anonymous world. In other words, creatives are drawn to locations that demonstrate certain Isovist properties which can be correlated with certain behaviour types.

The results of my study were significant in two ways. Firstly, the correlation between certain spatial configurations in cities and their success as productive, creative places has the ability to inform the way we build our cities now. If we can find correlations between certain configurations of space and the presence of successful and lively communities then we can start to build these configurations into our masterplans and building designs.

Secondly, my findings demonstrated that Isovist measures can be used effectively alongside narrative evidence to enhance our understanding of cities. The subjective experience of cities recorded by creatives seems to correspond with how scientific analytic methods predict cities to function. My research therefore demonstrated to me that an artist’s subjective experience of a place can play a significant role in understanding how a city actually functions.

[Alice Bates, February 2020]

My Relationship with the Isovist Software

My decision to use Isovists in my analysis was encouraged by Sam McElhinney, my dissertation supervisor and one of the founders of isovists.org. My use of the programme was transformative in strengthening my hypothesis and adding a scientific back bone to findings that were otherwise subjective and relatively abstract. I was blown away by the software’s ability to reliably flag up the precise locations of Hemingway and Kerouac’s favourite haunts as being places of particular spatial interest.

The power of ‘isovistics’ and Space Syntax combined is that it can provide more detailed and analytical understandings of the configuration of space. This is of particular significance to our understanding of cities. Firstly, the spatial configuration of a city shapes the way its inhabitants live- it controls who can see who or what in different spaces, which in turn controls how we understand the city. Similarly, the configuration of a city affects the way we move through it, which affects the people we meet and consequently also, the types of people we are aware of. The spatial configuration of a city therefore has a lot to do with both the forming of communities and the making of meaning in urban spaces. Studying Isovist fields allows us to analyse these very human phenomena in scientific terms.

I will continue to use Isovist software in my future research. My undergraduate thesis demonstrated to me that a well laid out city can provide a productive and exciting place to live for a wide range of people. There appear to be real recognisable spatial patterns that encourage creativity and the development of social networks. I believe thatIsovist.org’s ability to identify these patterns has the potential to change the way we plan urban spaces and develop new towns.

I have enjoyed using the isovist software. When used alongside subjective accounts of space and psychological understanding of the way humans respond to certain types of spaces, it provides a powerful spatial research tool. I would highly recommend it to anyone seeking to find out more about how successful space functions.

Comments